Meet the Team Behind the Paper: Carla Cannone and Elizabeth Tennyson on “Addressing Challenges in Long-Term Strategic Energy Planning in LMICs”

Carla Cannone and Elizabeth Tennyson are co-lead authors of a new paper that reveals critical gaps in the current approaches to energy planning in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs). The paper also introduces a framework to address these challenges. This research highlights gaps in capacity-building, data integration, and tool accessibility – key areas of interest to strategic partners, collaborators and fellow researchers.

What was the origin of your paper?

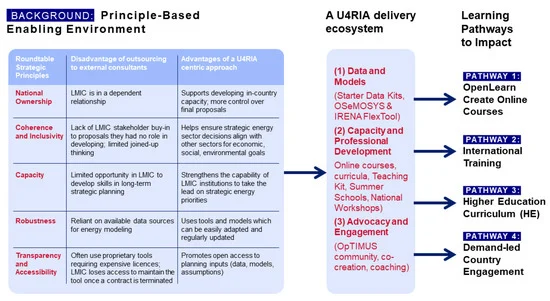

Carla: Our paper, “Addressing Challenges in Long-Term Strategic Energy Planning in LMICs: Learning Pathways in an Energy Planning Ecosystem,” emerged from years of observing the limitations faced by LMICs in their energy planning processes. External consultants are often brought in, creating a reliance that prevents the development of skills and long-term expertise locally. We saw a need to address this dependency, and our research uncovers the key gaps that exist between access to tools, data, and local capacity to use them effectively.

Elizabeth: The project was rooted in the realization that while LMICs have access to open-source tools like OSeMOSYS and IRENA’s FlexTool, there is a real gap in terms of a larger ecosystem that supports their continued use. We wanted to focus not just on tool dissemination but also on how to create a sustainable system that ensures these countries can take ownership of their energy strategies. This framework fills those gaps by focusing on national ownership, capacity building, and the need for coherence across stakeholders.

What are the main findings of the paper?

Carla: The paper’s core finding is that the current energy planning landscape in LMICs is fragmented. There’s a disconnect between the availability of open-source tools and the actual ability of local stakeholders to use these tools in a meaningful way. Our paper reveals gaps in technical skill capacity, data access, and institutional coordination. It highlights the need for a strategic, long-term approach that provides tools AND ensures that LMICs can adapt them to their unique contexts and challenges.

Elizabeth: We also found that many countries are missing the structured workflows required to integrate tools into their planning processes. Our framework addresses these issues by combining capacity-building efforts with co-creation of a context-relevant model that involves local stakeholders at every step. The framework we propose isn’t just about solving a short-term problem; it’s about creating a sustainable ecosystem where knowledge, tools, and resources are fully accessible, usable, and ultimately can be independently developed by local experts.

What does this mean for researchers, collaborators, and strategic partners?

Carla: For researchers, the gaps we’ve identified present opportunities for further exploration. There’s a need for more research into how we can better link data availability, tool usability, and institutional coordination to drive better energy planning outcomes. Collaborators and strategic partners can look at our framework as a starting point for improving how we engage with LMICs, not just by providing technical solutions but by focusing on long-term capacity-building and ownership. We very much welcome collaboration on creating data-sharing initiatives, refining open-source tools, and developing scalable training programmes that ensure long-term impact.

Elizabeth: That’s right. Our findings suggest that the traditional model of external consultancy isn’t sustainable in the long run. It’s too transactional and means that the local team are kept at a distance from the data and the modelling skills they need. A more sustainable approach is to empower local institutions (like government ministries and universities) by providing training on how to use modelling tools to produce analyses and scenarios, so that they can adapt those tools to their specific needs. Another benefit of that approach is that the modelling skills become embedded in each LMIC and can be used again in the future.

What were the most surprising aspects of the project?

Elizabeth: I was surprised by the widespread use of proprietary systems, which are costly and often limit transparency and accessibility. This really underscored the need for open-source alternatives and the critical importance of capacity-building, not just at the technical level but across entire energy planning ecosystems.

Carla: What surprised me most was the sheer enthusiasm and capacity for learning among local stakeholders when they were given access to the right tools and support. There’s a real desire within LMICs to take control of their energy futures, but the gaps in coordination and access to reliable data were greater than we initially expected.

What’s been the response to the paper so far?

Carla: It’s been overwhelmingly positive. We’ve already initiated pilot projects in Kenya and Zambia, where national institutions are working closely with our framework to develop their own energy planning strategies. International partners, including IEA, UNECA and IRENA, have also shown interest in using our framework to support broader energy transitions across other LMICs.

Elizabeth: Local governments, in particular, have responded well. They’re excited about the opportunity to take ownership of their energy planning processes. They see our framework as a way to build long-term, sustainable capacity within their own institutions, which has been a gap in many international aid programmes.

What will happen next in terms of developing your findings?

Carla: We’re currently focused on extending the framework to more countries. We’ll continue refining the process based on lessons learned from our pilot projects. We’re actively seeking collaborations with universities and international organizations to provide the training and support necessary for these countries to fully implement the framework.

Elizabeth: We’re also looking at how to better integrate the framework with financial mechanisms. One of the biggest challenges LMICs face is in securing climate finance. We hope to use the models and data generated through this framework to help strengthen their cases for funding, ensuring that energy transitions can be financed and sustained over the long term.

The Strategic Viewpoint:

Vivien Foster, International Partnership Director adds: : This paper fits directly into CCG’s mission of fostering sustainable, inclusive development. By addressing the gaps in capacity, data, and coordination, we’re helping countries build energy systems that are not only robust but also aligned with global climate goals. This framework supports CCG’s broader vision of empowering countries to lead their own energy transitions, rather than relying on external expertise.

Yacob Mulugetta, Partnerships Director and International Engagement Lead adds: CCG has always focused on transparency, accessibility, and long-term capacity-building, and that’s exactly what this framework delivers. By equipping LMICs with the tools and knowledge they need to drive their own energy transitions, we’re directly contributing to CCG’s strategy of building low-carbon, resilient energy systems that can withstand future challenges.

A project like this obviously involves a lot of people and has far-reaching impact. Tell us more about the support you received from across the sector.

Carla: Absolutely. I’d like to thank all my co-authors: Pooya Hoseinpoori, Leigh Martindale, Francesco Gardumi, Lucas Somavilla Croxatto, Steve Pye, Yacob Mulugetta, Ioannis Vrochidis, Satheesh Krishnamurthy, Taco Niet, John Harrison, Rudolf Yeganyan, Martin Mutembei, Adam Hawkes, Luca Petrarulo, Lara Allen, Will Blyth, and Mark Howells. Their collective expertise and dedication were essential in uncovering the gaps in energy planning and developing the solutions we proposed.

I’d also like to highlight the contributions of Luca Petrarulo, who led the Roundtable Process.

Elizabeth: We were also deeply supported by the OpTIMUS community, initiated by Mark Howells and Holger Rogner, which played a crucial role in maintaining the energy modelling ecosystem. Mark Howells deserves special mention for his leadership in establishing the Energy Modelling Platform (EMP) and the ICTP Sustainable Development Summer School. Many of the modelling and capacity-building activities that informed this paper are rooted in these initiatives.

Our collaborators from KTH, including Eunice, Ioannis, Vignesh and Constantinos, were key in developing EMP-Europe and EMP-Africa, and their contributions were instrumental to our success.

We also benefited greatly from the support of international organizations like the African Development Bank, the International Energy Agency, the International Renewable Energy Agency, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, the International Atomic Energy Agency, the World Resources Institute, and the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office. Their collaboration and partnership were crucial in bringing this work to life and extending its impact. We couldn’t have done it without these incredible individuals and organizations.

Finally, thanks to the Kenya energy planning team – their support and collaboration is what made this initial work possible, and we are looking forward to continuing to work with them side-by-side as they advance on their energy transition and low-emissions journey.

Read the paper here: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/16/21/7267