Women in Energy Modelling Webinar proves a great success.

On 23 October CCG held a webinar called ‘Women in…

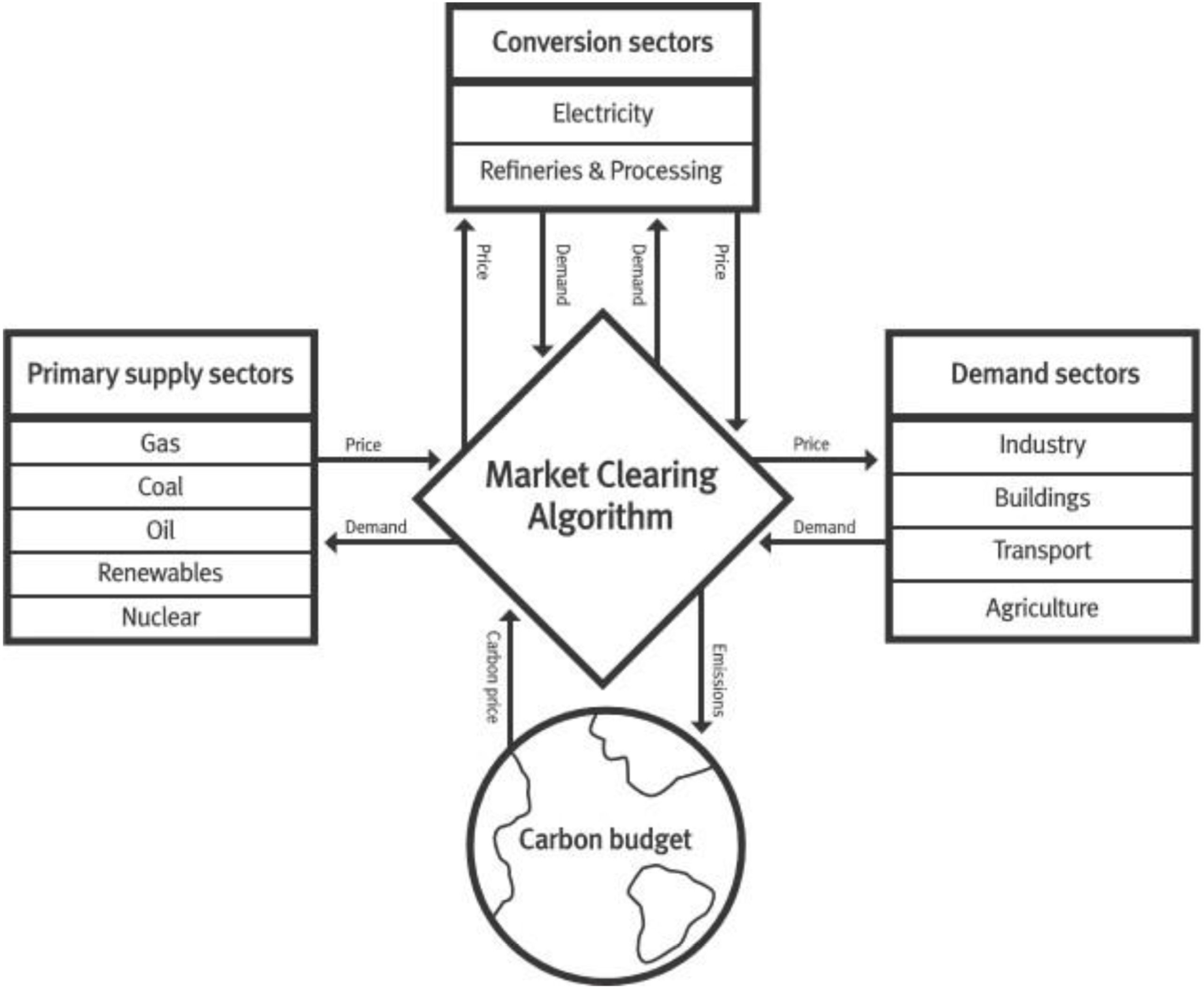

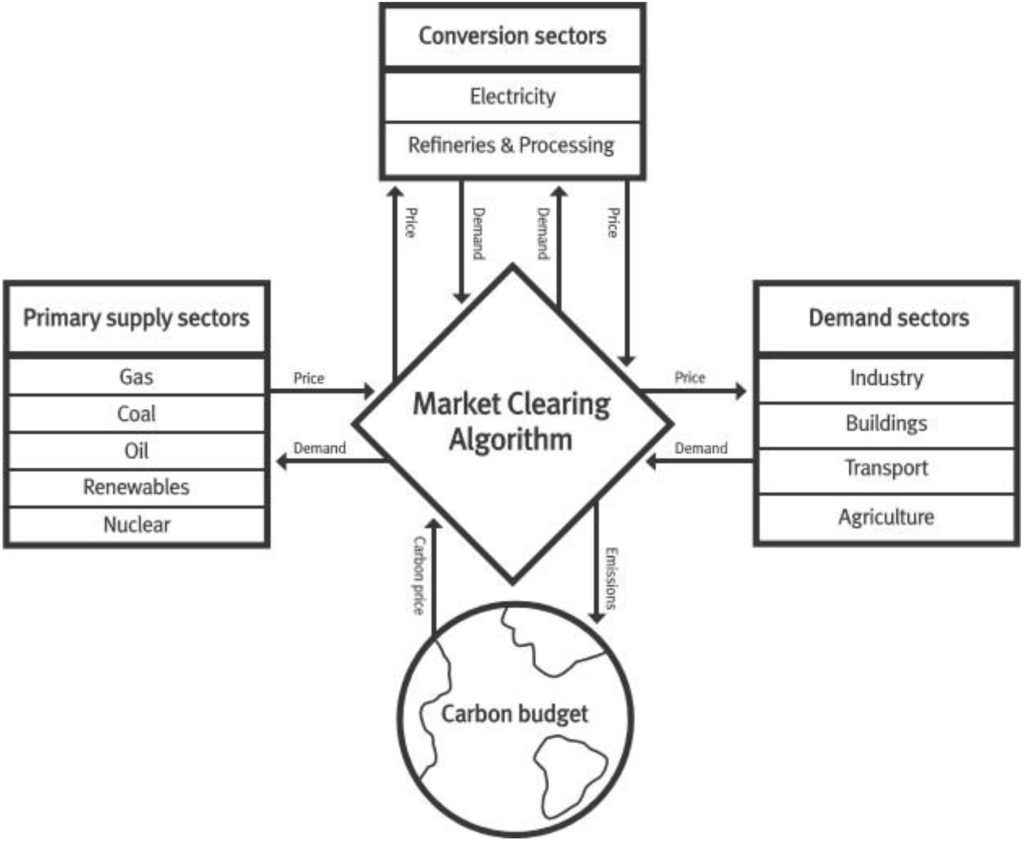

CCG Director of Research, Adam Hawkes, is part of the team which wrote the above paper presenting MUSE, a new modelling framework which has been successfully trialled in the UK and Brazil. The other authors are Sara Giarola, Julia Sachs, Mayeul d’Avezac, Alexander Kell,

In terms of the origins of this paper, did something particularly trigger you to do this work? I’ve worked in energy systems modelling for quite a while, and I saw a gap. Most models out there are normative: They’re rather idealised about transition scenarios. So that is the impetus for this, which I think is described quite well in the paper. It says that as we move from planning towards real implementation, we need to understand how to achieve these pathways as opposed to just what the pathway is.

Yes, and the abstract mentions the urgent need for tools capable of more realistic interpretation of the energy transition, capturing human behaviour, and so on. What do you think are the most important factors now to try and include into modelling so you can get a more realistic interpretation as human behaviour is a very broad topic, isn’t it?

I would start at a much more basic level because the world is a very complex place, and there are a huge range of factors which impinge on the direction things may go, way too many to model things in a predictive way. But the level of understanding of energy transition pathways is still limited at the moment. So, I would take baby steps towards more realistic scenarios. The first step I would take is looking at distributional impacts. Get a better, more representative, disaggregation of populations and look at how the cost of a transition impacts on each tranche, if you like, within the population.

MUSE has two broad features in this regard: one is that you can tell it how consumers and firms make decisions. You can say you have certain decision rules and constraints. (It’s super interesting from a social science point of view.) But it’s difficult in that the data to support that is basically non-existent at the scale we need. That kind of data typically needs techniques like stated preference or revealed preference which are from the realms of social science. But they’re expensive to deliver as they require surveys, and they’re also not always be very accurate for simulating the future.

So that decision making part of MUSE is a tough research area. But MUSE has this other angle, which is simply simulation of the investments and looking at how these impact different population groups based on their income or savings, their access to technology and so on. It’s a much more nuanced and granular look at those features of a transition as opposed to worrying too much about the decision-making processes.

And do you still have to try and acquire that data?

We have better data for that kind of thing. Obviously, the context CCG works in means that data is often challenging because in many countries just don’t have much data, or the data you have is not good quality. That’s why we have another stream of work, which is about building better data sets, based on novel spatially and temporally granular data sources like satellites.

Looking back at this project, what was the most striking thing for you?

Well, the project is still ongoing, and the area of study is not going away anytime soon. We’re building MUSE 2.0 now in a different programming language, with a slightly different approach. I think the learning is firstly how difficult it is to depict real transitions. We have to be honest and admit that this is not as accurate as we want it to be, and there are lots of things we would like to improve. It’s about an iterative improvement of this space, so that we can give policymakers better information in time.

Do you feel that future iterations of MUSE will involve more formal involvement of social scientists or geopolitical specialists to build develop the realism factors in this model?

We certainly could go that direction, but at this point the involvement of those disciplines is more at the application end of the model rather than at the framework building stage. We’ve built in a lot of flexibility to MUSE so it can cope with a lot of different possibilities, and that’s where you can bring in social scientists and geopolitical realities in order to get the framework to depict a real transition. So that is something we do.

Our colleague Steve Pye did a project recently working with a geopolitical team from Warwick who brought that new dimension to energy modelling. Is that a trend, would you say, that people are looking for more nuance, more granularity in the outputs of their modelling?

Absolutely. There is a slight dismay in the modelling community about how transitions are depicted and the headline messages that are used because these sometimes give people an unrealistic view about what is possible and which direction the world should head.

If you look at the IPCC scenarios, what you see is this radical decline of fossil fuels followed by, or in tandem with, a radical uptake of carbon removal from the atmosphere; this is the headline picture. Both of these come with incredible just transition issues, and the potential for great socioeconomic and macroeconomic upheaval, alongside serious technical plausibility questions, particularly around the carbon removal.

One the one hand, important to have a picture which shows a pathway to the objective of well below 2C warming. But I think this needs to come with health warnings about how realistic it is, and we should as much as possible move towards better understanding of the feasibility of the pathways presented.

Particularly when you have a president coming in saying he’s going to “drill baby drill”. He’s not going to move away from fossil fuels any time soon.

You mention the incoming president and I think that’s a good point to make, because there is a reason he won. When we model energy transition pathways, we need to be acutely aware of the possible impacts of those transitions on the population. Because if a government does things – maybe based on our modelling – that don’t resonate with its people, they’re going to lose the battle for hearts and minds, and the next election. It would be better if climate change mitigation does not become a political battleground.

What would you like this paper to what impact would you like this paper to have? Who would you like to take notice of it and to respond to it?

I would like policymakers to look at it and recognise the difference between this type of modelling and the type of modelling they currently use, which is often the more idealistic version. And I would like the modelling community to recognise that more work needs to be done to add granularity and realism to transition scenarios.

Thanks for talking to us.

The full paper can be found here.

The authors thank the Sustainable Gas Institute (SGI), CCG, and the EPSRC (grant EP/R511547/1) for financial support. Also Dr Cheng-Ta Chu, Dr Sara Budinis, Dr Ivan Garcia Kerdan, and Dr Daniel J.G. Crow for the contributions to the theoretical framework of the MUSE model. And the Research Computing Service of Imperial College London, especially Dr Diego Alonso Alvarez for contributing to the MUSE model release.