Sukriti Sharma is a PhD student working on hydrogen systems in India. The past twelve months have been very successful for her, seeing her hard work rewarded publicly. She won first prize for her hydrogen poster at an event hosted by the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy MNRE in Delhi. She also attended an OpTIMUS community Summer School in Trieste where she won a prize for best presentation as part of the MARIO track. She is clearly a person who has a bright future ahead of her.

Where are you based at the moment and what are you working on?

I’m a PhD student at the Indian Institute of Technology, Ropar, in the north of India. I joined after completing my bachelor’s and was able to skip my master’s because my scores were high. I am in my final year now.

What is the focus of your PhD?

I am in the Department of Chemical Engineering, and I’m especially focused on hydrogen systems for India.

Tell us more about that.

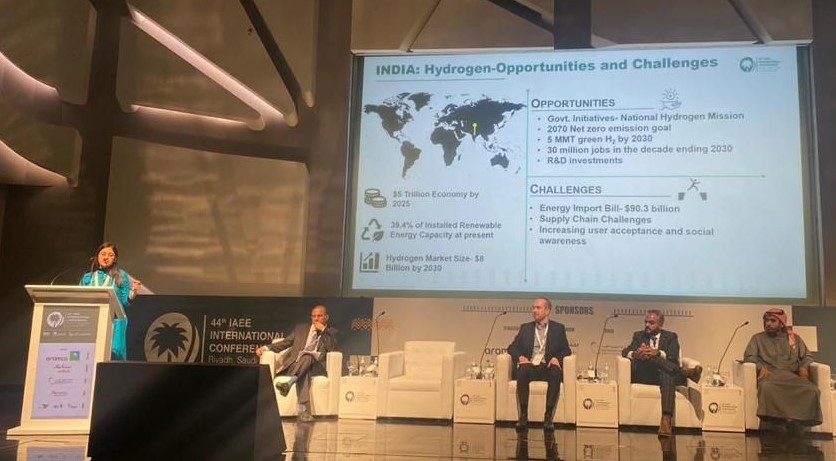

I am working simultaneously on three to four problem statements. The broader topic is the modelling and analysis of hydrogen infrastructure for India. Earlier on it was focused on production sites for grey, blue and green hydrogen, but the policies of India are now more aligned towards green hydrogen, and we have the national hydrogen mission which was announced in 2021. So, my work includes carrying out the techno-economic feasibility of these three production pathways.

For anyone who doesn’t know, grey hydrogen is made from natural gas. Blue hydrogen involves carbon sequestration, capture and storage, but it is not supported as much although it has good cost benefits. Green hydrogen is made through electrolysis and doesn’t produce any emissions.

I am carrying out the techno economic analysis of these methods and the numerical modelling of pipelines. This includes looking at how the natural gas pipelines can be made feasible for hydrogen transport through blending with natural gas.

Is India’s plan to keep the hydrogen and use it itself, or is it hoping to export hydrogen as well?

Right now, our energy import bill is huge, around €90 billion. We import a lot of coal and natural gas. So, with this national hydrogen mission, we are planning to first make India self-reliant and then to export as well.

Is India looking at any other sources of clean energy or is it putting all its focus on hydrogen?

We have a big focus on solar energy as well, so recently there was a government scheme that was announced for free rooftop solar panel installations for some households. There are infrastructure challenges and also storage challenges that are being faced, so it requires huge capital investment.

Let’s talk a little bit about you. Can you tell me about your early life, your family life and your education?

I come from a hill state – Himachal Pradesh region in the Himalayas. When I was say 13 or 14 we started experiencing some of the climate change effects. There were changes in snow patterns with the snow coming in February rather than December. And during the monsoon season there were huge amounts of floods and landslides. Lots of families were affected and I lost my friends in that landslide area. So, yes, I am someone who is personally being motivated to pursue a career in the climate change area.

Which subject did you study for your undergraduate degree?

My bachelor’s is in chemical engineering and, again, my major project was on modelling and simulation of bio-gas plant infrastructure for Himachal Pradesh.

Did you choose that because you were interested in climate change or because somebody inspired you to look at that area?

I used to read magazines and newspapers and it interested me. And climate change is something very personal to me.

Let’s talk about women in climate change. What kind of obstacles have you come across in the progress of your studies, because you are a woman?

None, really. There have been certain gender parity issues like the ratio of men to women in my chemical engineering classes – there were ten girls and 70 boys. But there weren’t any challenges or obstacles.

I’m glad to hear that. So, do you think that perhaps your generation is better at viewing men and women equally than maybe my generation is?

Yes, I would agree with that. My family did wonder why I chose chemical engineering as it’s dominated by men, but those challenges are for past generations; in this generation, I guess we can look at it with a more equal perspective.

Well, I’m glad. I’ve seen from your profile on LinkedIn that you have been very successful in winning prizes for your work. What kind of support do you have in your life?

The greatest support I have had has been from my PhD supervisor, Asad Sahir. When I entered in my first year, he told me that I should not confine myself to the lab area but explore and see the global perspective. He’s also associated with the Society of Women Engineers (SWE) in India, so I got associated with that programme through him.

How does the Society of Women Engineers help?

There are few women engineers, so I’m part of this grad SWE programme. I get to attend the conferences of the SWE India programme in which they invite women leaders, especially the ones who have faced many challenges, and there are lots of inspiring stories. They’ve also supported me with funding for travel.

Why is it important to have women involved in the work to tackle the climate crisis?

Because we are equal. We are equally responsible. It won’t be possible to tackle climate change effectively if only 50% of humanity are involved. It has to be 100%. And women can contribute to so many aspects, which can help address this issue.

What unique qualities, if any, do you think women bring to discussions around solutions and innovations as far as the climate is concerned?

I can think of their role as caregivers because women are caregivers. They are also good community leaders.

I get the feeling that you don’t believe that that’s the main reason. Is it rather that climate issues should be tackled equally because men and women should be equal?

Yes. I would stick with my first answer that yes, it should be 50:50. I am 24, so I am not at that point in my life where I am a caregiver so I can’t think from that perspective.

I think that’s a fair answer. Now, I know that you attended the ICTP Summer School in Trieste last year, how was that?

It started with a CCG team visiting my institution for collaboration. I met Lara Allen, Elizabeth Tennyson and others. My supervisor told me about this upcoming opportunity, so I applied for it, got selected and was on the MARIO Lifecycle analysis programme. I was the one who was from India and the rest of the group were from different corners of the world – Nepal, Tunisia, Ethiopia.

So, my problem statement was the life cycle analysis of hydrogen production pathways for India. I looked at grey, green and blue hydrogen, interestingly, the same work I’m doing right now. My results were very interesting, and I won the best project award in the Mario Track at ICTP for my work.

One of the interesting things was that my results showed that for one KG of green hydrogen production, there is 2.2 KG of CO2 emissions. Then the Government of India released this new notification in November that for one KG of hydrogen there should be 2 KGs of CO2 emissions. So that was a great validation for my results; my number was 2.2, the government number was 2. They were very interested in how I reached that number.

One of the things we talk about a lot is data because obviously you can’t do energy modelling without data. In your situation in India, is there already a lot of data available or did you have to generate your own or get it from other places?

If I talk particularly about MARIO, there was lot of open-source data that was available for India. But my counterparts from Nepal, Tunisia and Ethiopia had to face some data related challenges. For me it was quite disaggregated and scattered but there was lots available.

Tell us about your success with UNESCAP

As I mentioned, I come from Himachal Pradesh. It’s a hill state which is aiming to become the first green state of India. I carried out the analysis for how we could harness hydroelectric power because there are lots of rivers and fresh water sources available in Himachal Pradesh; we have four major river systems. So my question was how we can use hydroelectric power to generate hydrogen and then make it a greener state?

This project got selected and I went to UNESCAP in Bangkok. That experience helped me to understand how different policymakers think because there were people from all of South Asia representing every point of view on climate change.

The former executive director of the IEA was there – Mr Nobuo Tanaka – and I asked him how we would know in the future when we had reached the point at which no more actions would be needed on climate change. He answered that it’s a never-ending quest; you have to just work, work, work. So that inspires me as well.

And did your work for UNESCAP lead to something?

Yes, SJVN – an organization in India that deals with Satluj River hydroelectric power – came to our institution and they were shown my work, and a training programme was organized for them.

Well done. More generally, as a 24-year-old person, looking at how the world is tackling the climate crisis, is there anything that you think they’re missing or they’re doing wrong, or you wish they would focus on instead of some of the things they’re talking about?

I feel that, rather than more dialogue and diplomacy, we should focus on implementation. That is more important because climate change is real, and it’s happening every day, and we cannot just waste our time in dialogue and diplomacy. We should come together because it’s something which is about the whole world.

There is one more thing that I would say and that is that climate change is an interdisciplinary issue as well. So it’s not that only policymakers should focus on it, or the ones who are good economists; everyone has to be equally held responsible to solve this problem.

OK, excellent. If there are some girls in India who are about to finish school and thinking about working in the climate sector, what would be your message for them in terms of whether they should do it or what challenges they might face?

I would say that definitely they should go ahead because lots of opportunities are waiting for them ahead in this area now and it would be good if more and more people would come together and address the issue. The more people we have, the better it gets and the more expertise we have.

One thing I noticed from LinkedIn and from our conversation today, is that you haven’t talked particularly about any other women who have supported you and I wondered if that was the case?

My family, especially my grandmother, inspires me a lot and my mother as well. My grandmother inspired me because she was always telling me that women have to push themselves forward and they have to become independent. They should not, in any sense, be dependent on men.

From the very beginning, I have been told these things by her.

Very, very wise words from your grandmother.

Sukriti was speaking to CCG’s Peter Allen. If you are a women working in Climate Change or would like to suggest someone for an interview, please email p.allen2@lboro.ac.uk.