New approach offers more certainty in the take-up of clean cookstove alternatives to charcoal

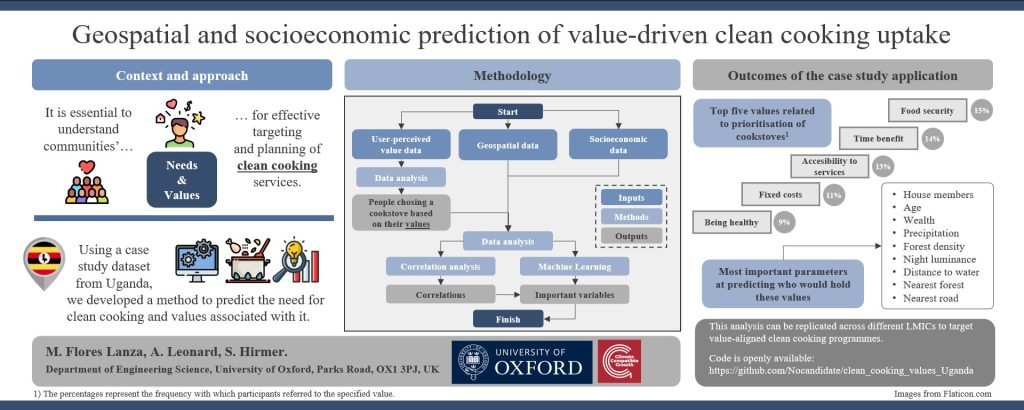

A new paper – Geospatial and socioeconomic prediction of value-driven clean cooking uptake – describes a study that takes a first step towards enabling energy service providers to target areas with a greater likelihood of uptake based on open-source datasets. Although the example here is in Uganda, the proposed method can be applied for different geographies and energy services. The paper is called “Geospatial and socioeconomic prediction of value-driven clean cooking uptake”. It was written by Micaela Flores Lanza, Alycia Leonard and Stephanie Hirmer. Here, Micaela explains more:

What is the background to your paper?

There are many programmes that distribute gas cookstoves to towns and communities across Sub-Saharan Africa, in an attempt to reduce the use of charcoal and wood in cooking. But those programmes are not always successful because the needs and values of the people receiving them are not taken into account beforehand.

I see, so not having the right information about how people might use them or need them undermines the effectiveness of them.

That’s right.

What was the origin of the paper?

I was very interested in working with CCG’s Alycia Leonard and Stephi Hirmer and they proposed that I focus on analysing energy needs in Sub-Saharan Africa, from the point of view of just one domestic item otherwise the scope would have been too broad. So, I focussed on gas cookstoves rather than fridges or televisions and so on.

After doing some initial research, I found that there was a lot of information about these cookstove programmes in Africa and that revealed that many of them didn’t succeed. With that information, I was able to undertake this project.

There seems to be a move away from generalised data to more detailed data, I’ve noticed. Another project – MUSE RASA – has obtained data on energy demand for every square kilometre on a global scale.

One of the things your paper mentions is the values closely related to cookstoves which included food security, time benefit, accessibility service, fixed costs and being healthy. Can you tell me a little bit more about that?

Yes, this is related to Stephi’s PhD thesis, where she researched the relative importance of domestic electrical items to people in Uganda. So, for example, someone might choose a cookstove and a fridge and the reasons they choose these create the values that we use in this project. A fridge, for example, creates ‘food security’ because it allows you to store your food until you need it. The use of a stove prevents you from breathing smoke produced while using charcoal, so this enables you to “be healthy”.

I understand. What about the other values like forest density and night-time luminance?

Some of the other parameters that proved most important in predicting whether people would accept cookstoves were things like forest density and night-time luminance. The first one indicates whether those people have access to charcoal and wood to burn. Night-time luminance was an indication that electric power was present in the area so that would mean adopting electric cookstoves could be relatively easy. We used machine learning algorithms to predict all of this.

“Getting it wrong can mean a lot of wasted money and effort. Getting it right by using this data, can make a real difference and it saves you time because you don’t have to undertake your own in-situ surveys to obtain the data.”

So, who ideally would you hope would use this paper?

I think that governments would find it useful when launching programmes because it will help them to determine which areas are the most needful. This approach can be used in any location, it is not specific to just one place. Also, it can be used by other academics because it points to other work that needs to be done in this area.

I guess that the tangible benefit to governments is that they can target their efforts more efficiently and avoid wasting their investment in areas that can’t or won’t use cookstoves.

Exactly, as we say in the paper, approximately 2.6 billion people lack access to clean cooking services with 82% of those in sub-Saharan Africa and 94% in rural areas of this region being affected. This research focuses on Uganda, where approximately 45.5 million people rely on traditional cooking technologies and fuels for cooking. 76% of these live in rural areas. So, with these kinds of numbers, getting it wrong can mean a lot of wasted money and effort. Getting it right by using this data, can make a real difference and it saves you time because you don’t have to undertake your own in-situ surveys to obtain the data.

The full paper can be found here: Geospatial and socioeconomic prediction of value-driven clean cooking uptake – ScienceDirect