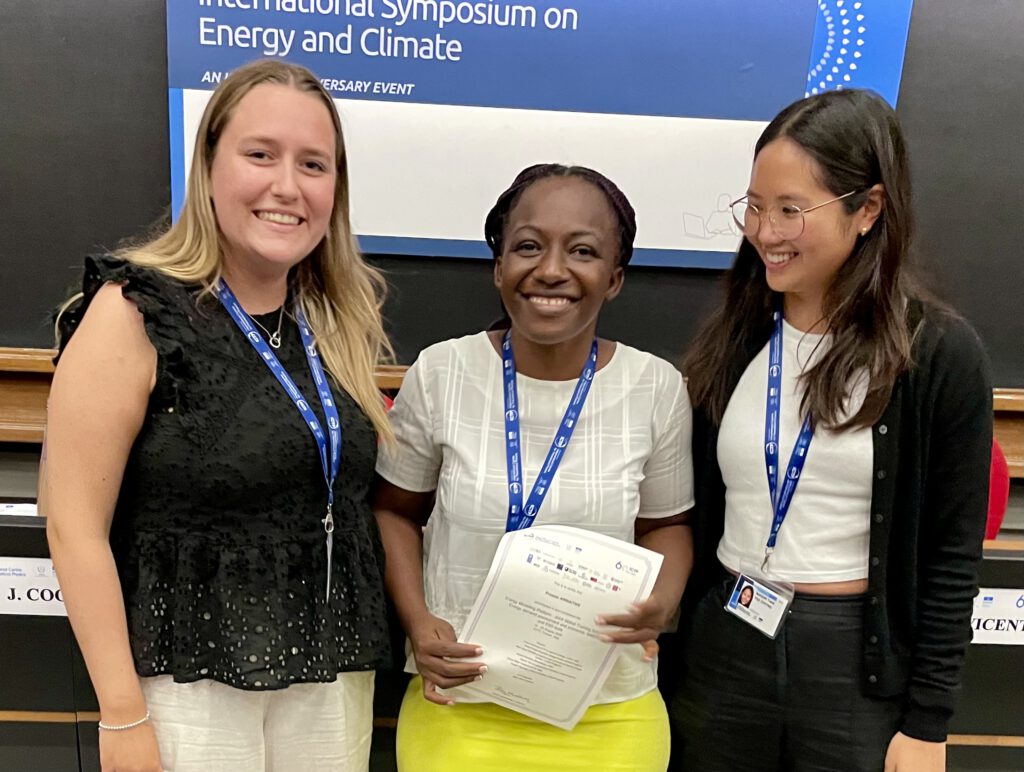

Arinaitwe Prossie is a Power System Engineer with the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development, Uganda. She works mainly in the Rural Electrification Department which was formerly the Rural Electrification Agency. It has now been mainstreamed into the Ministry as part of the ongoing power sector reforms in Uganda. ‘Prossie’ followed the MAED track at the EMP-G in Trieste in September 2024 which is where she spoke to CCG’s Peter Allen.

How do you come to be here?

Initially, a friend shared the link online and I engaged my government. They were interested in the energy modelling training and recommended me to CCG for funding. Some of my colleagues had already done the training in other tracks.

And how have you found the experience so far?

To me, it’s really an interesting one because for so many years, we’ve been modelling demand based on manual tools. This was the first time I’ve had a software tool for estimating the actual demand, especially for the industrial sector.

And how easy is it for you to learn to use?

It’s easy if you have data. It requires a lot of information. It requires a lot of coordinated planning across the sectors. But also, it requires patience. You need to understand the start and the end point, especially where your country is going. You need to know the direction of your country.

Have you always had access to data in your job?

There are a lot of gaps. The data is scattered in different places or missing, so you have to do more individual interviews to get it. But also, it doesn’t address most of the questions. For industrial issues, it’s hard because our country has been focused on household or residential electrification. We are just transitioning to the productive use of power, so the data relating to the existing equipment, machinery, is really not available.

I see, and is there an energy plan for the country, or is your work part of writing one?

We have an energy transition plan, which we designed with the support of IEA. And we are looking at using clean energy as an enabler of industrialization. In addition to the existing policies for access and renewable energy technologies, we are focusing more on how to switch Ugandans, who are mainly peasant farmers, into productivity.

Do those farmers have access to electricity now?

There are access interventions, which are already under implementation, but they are still low. We still have a long way to go in expanding our grid, both transmission and distribution which are the main determinants for access. For the isolated areas like islands, we are implementing more mini-grids.

Right. What kind of industry is there in Uganda?

The majority are agricultural, small-scale millers, scattered across the country. We have never really looked into energy strategies for that category of people, and they are growing at a very fast rate. It’s mostly crops such as maize, cassava, peanuts but also juice processors, milk dairies and coffee millers. Those are the categories in agriculture.

What are they using currently, and what do you hope they will use in the future? Currently, most of the motors they use range from 60 horsepower to 100, powered by diesel. There are areas where we have extended the grid to medium sized enterprises, but now there is a challenge with the motor: although electricity is cheaper than the diesel, the electric motor doesn’t fit their other equipment. And they are reluctant to change because they’ve already invested in a motor. As a country, we don’t yet have a strategy on how to transition them from this diesel-powered motor to an energy-efficient motor.

So there need to be financial incentives for the farmers to take those things on?

We have a challenge in that first we need to model the energy and know how much the farmers are going to consume over a period of time. Then we can see which incentives might work: financial or technical; do we replace the motor itself?

We had a similar situation with household where the meters were postpaid, and that was the main constraint. So, we switched to prepaid and solved the problem.

Are there many people who know how to do energy modelling now in Uganda?

I think in the Ministry there are only three. I don’t think there are many in the other department because most of them are focusing on electricity. We have very few who know how to now integrate electricity with other energy forms.

I see. Do you see a role for other models here, other tracks for your colleagues?

Quite; not only colleagues, but also students. I’m looking at it being more of a capacity building solution for the universities. So that we receive them when the students are already prepared.

Yes, so the universities teach it as part of their curriculum.

Yes, because most universities in Uganda, they do one-year research at undergraduate level. So if they could use the models, learn them and come into the sector when they know how to use them. We especially need them in the energy design, energy conversion and electrification sections. It’s important that our professionals are trained in most of these tracks, especially MAED, OSeMOSYS, the Energy Explorer model and FINPLAN to look at the cost implications.

There’s a Flatpack that we do, with modules for energy modelling that universities can integrate with their courses. Strathmore University is the first one that’s going to take some of our modules and put them into a master’s degree that they offer.

I had not heard about it before yesterday’s presentation, but I am impressed that there’s a solution students can use. Unlike in developed countries where the software is available, in Uganda it’s more of who you know that has the software. Even the universities don’t have it so I think they will be interested.

Well, that’s part of our plan, to try and create that legacy so the skills and the knowledge are embedded in your country.

Let’s talk now about how you got to this place in your career. As a woman, it’s still quite unusual. Where did your interest in this area start?

My interest in engineering started when I was really young, and my father was able to see it very early. I had a lot of passion for mathematics and the sciences. He mentored me in the direction of loving numbers. My teachers also saw my strength and they would encourage me. I made a decision in my secondary school to go for engineering, and I eventually settled on electrical. I’d come from a rural country area which didn’t have electricity at all, so I had always wanted to put the lights on. I opted to train in rural electrification despite the country having better companies, because I wanted to know if I could put electricity in my village. I ended up learning a lot about electrification, dealing with almost all districts in the country for over 10 years.

And it’s from there that I started looking at new solutions. How do you use electricity to improve the lives of Ugandans beyond just extending the grid? Because through my work, I’ve managed quite a number of projects, and they usually reveal social issues alongside the technical ones. So, you see community change in terms of education and health. Because of these electrification projects, I’ve seen the impact, but I’ve also seen the challenges when power goes off.

To my mind, it’s about how you help this poor Ugandan who has just received electricity and what they can do with it. So, I switched from just connecting to thinking what it could be used for. That’s how I ended up identifying a small medium enterprise requirement for electrification, and the productive use of power. That’s the reason I’m here now.

And did you do all that in your professional life as a government employee or did you start in other places in your professional career?

I’ve not worked in the private sector. Right from university I was recruited by the government as a temporary employee since during in my final year undergraduate studies. I had designed a mini-grid project for electrification of a small island in Lake Victoria in Uganda. I have been progressing ever since, learning, designing and implementing new national projects. That has been the journey.

How do you feel about the progress that Uganda is making on its clean transition? Are you optimistic about getting there? What things need to change to achieve success?

Every day I see a new solution. As an engineer you’re seeing problems as a solution. I still feel we need to do a lot of mentorships for young people as a means of transitioning the knowledge and the experience to the next generation. A lot of mentoring is required to get us where we need to get.

And what’s behind that generation of mentors not passing on their knowledge?

It’s about them not really engaging. They have the skills, but they get busy in their day-to-day person work, so there isn’t time to train. They would need to make time especially to do that. But also, as a young country, we are just beginning to see this older group as a resource. It’s not been like this before. We have not yet planned on how to get them to become consultants instead of leaving them to retire into another totally different industry.

Yes, I understand.

I’ve been seeing most of them going into farming when they retire from energy and all the knowledge and experience they have totally goes to waste. We need to look at how we bring them on board to mentor or as consultants.

That’s fascinating. Thank you for talking to us.