Jessica Omukuti has recently joined the Smith School team at CCG, working alongside Prof Sam Fankhauser, Jessica’s broad focus will be on gender and social inclusion (#GESI) within CCG countries, and she will be starting with Zambia. Here she shares her plans and broader observations on the issues she researches

Welcome to CCG. What will be the focus of your work? I’ll be thinking mainly about how renewable energy entrepreneurs (i.e. businesses involved in the provision of renewable energy) are designing their business models to meet the needs of those who are poor and marginalised. I will also speak to government representatives to understand how they are engaging with renewable energy entrepreneurs. My understanding is that the government is very keen to expand renewable energy provision. There’s been a drought in Zambia and rolling blackouts and so we expect a high level of awareness about the importance of renewable energy. There’ll be a lot of discussions about energy access and security amongst the public, and among the renewable energy entrepreneurs. I expect a lot of political conversations on the topic and a lot of demands from the energy entrepreneurs to help them reach those who have been affected by the blackouts.

How will you find those entrepreneurs and which aspects of GESI will you explore?

I’ve reached out to the Zambia Renewable Energy Association (ZARENA) and the Solar Industry Association of Zambia (SIAZ) as well as the Ministry of Energy, various CCG contacts and social media. I know that mostly entrepreneurs are concerned about those at the bottom of the pyramid so Social Inclusion will be the main aspect but other aspects such as disability may come up.

OK, let’s got a little further back now. Can you share with us some of the highlights of your career so far?

I was trained as a climate scientist and then I slowly started moving away from the science into the social science of it and that’s grown over time. I’ve shaped my career to be much more rounded around issues of equity and justice. I work on understanding how net zero transitions can be implemented in low- and middle-income countries. I’ve previously (and still work) on topics related to climate finance. I’ve applied that at different levels and worked with NGOs, governments and international institutions.

One of my greatest accomplishments is getting the job that I have today, working on equity and justice in net zero, which is something that I’m passionate about.

Also, in 2022 I was appointed by the UN Secretary General to be a member of the High-Level Expert Group that made recommendations on how to make net zero commitments by non-state actors more credible. That was a highlight because it was an opportunity bring in all the research that I’d been doing over the years and integrate it into a very high-level document that would guide action on net zero. We covered energy, transport, equity and justice governance, the role of carbon credits, the role of financing and so on. I’m also leading work in other parts of developing world. For example, we have an ongoing in India, Mexico and Kenya, looking at the role of businesses in transitioning to net zero.

What’s your sense of the traction that equity is getting?

Governments in developing countries have been talking about equity and justice quite a lot. At the international level, climate change stakeholders acknowledge that they need to achieve equitable and just transitions, but action has been very delayed in catching up with that recognition. We find that agreements like those at Conference of Parties (COP) do not fully reflect the need for equity and justice, and that the implementation of these actions is not reflective of the importance that needs to be given to these issues.

That’s a common belief, I think. So how do your rate the world’s response to the climate crisis? It still seems very slow to me and held back by various factions who don’t really want to change.

Yes, there is very slow progress. Whatever is happening to households and individuals is not reflected in decision making at the national and international levels where we have most of the policy making and implementation happening. So there’s a huge gap between the needs and the action that is being done. I think one of the reasons for that is because climate change is a very political process. The science is quite clear about what is needed, but then the decision-making part of it has been very much politicised. I mean, climate action is naturally political because it’s intertwined with development, emission reduction, adaptation, resilience and so on, but then there’s been a lot of inertia at different levels to implement some of the actions that are needed.

For me, the key to unlocking action is finance. Research has found that there are already very strong policies and guidelines on what we need to do to stay within safe climate limits. We’ve seen businesses making commitments and countries setting targets, so there is progress on that aspect. But then there are just not enough resources to fund some of this work. Governments and the private sector should think a little more about how to mobilise the needed resources to implement these policies and plans.

What do you think is holding the finance back?

I think the issue is that the global systems for finance are just not aligned with the needs of places that are most affected by climate change. For example, we have the multilateral development banks (MDBs) which could easily turn the tide by financing transformative climate action, but their priorities are just not aligned with the needs of developing countries that are suffocated by climate change. They direct funding towards areas that have are less effective at addressing the climate crisis.

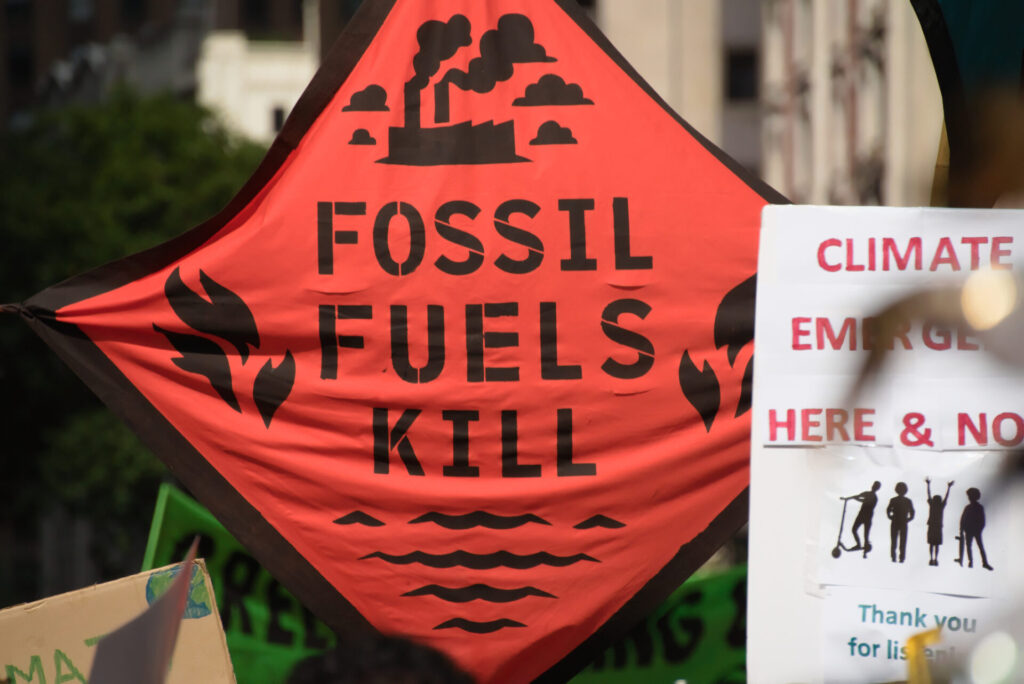

Even though other financial institutions such as banks say that they’re going to net zero, they’re still allocating finance towards fossil fuels. This is the disconnect between the intention and the outcome.

So, is it that the financial infrastructure is no longer fit for purpose for the new challenges? I have read that many potential investors are very risk averse for example. What needs to change there?

It’s exactly as you’ve said. It’s attitudes, but also the risk appetite by investors needs to change. The world is not as it used to be. We cannot expect the same returns from investments as we used to do thirty to fifty years ago. Investors need to account for that, and they also need to have a social responsibility towards those that have been affected by climate change. So, it’s patient finance where they wait longer for a return on their investment but also finance that has a greater risk appetite. If you used to get 20% return on investments, you should be willing to get slightly less return for your investments.

So they need a balanced portfolio in terms of risk, where some things might not do too well but others, even with a smaller return, would provide a great return because of the scale.

Yes, but it’s also about making social investments, impact investments with the goal of generating a common or global good by addressing climate change. Right now, there should be more investments made with the explicit goal of addressing climate change. It’s not just emission reductions; it’s also ensuring that communities are able to adapt. Today, we are seeing lots of investments go towards emission reductions, but not towards adaptation. This rebalancing needs to happen at the global level, and the sectoral or thematic level.

I see. If those countries don’t have enough resilience to get through the severe impacts of climate change, there won’t be any ‘future markets’.

Exactly. We need to see climate action as conditional on adaptation, mitigation, averting loss and damage and achieving development outcomes.

Finally, is there anything else you will be working on as part of CCG?

Yes, after working on the renewable energy entrepreneurs, I’ll be exploring critical minerals and how informality is represented and addressed within that space. It’s something that I’m also quite excited about.

By informality I mean the ‘casual’ workers who extract the critical minerals and the structures that are put in place to protect them, or not; how they’re managed, and what can be done to ensure that they are much more recognised and that they benefit from the industry. There will be a gender and social inclusion component to that work too.

Thanks very much for speaking to us, Jessica, we wish you success in your new role.