“I didn’t choose energy modelling. Energy modelling chose me, and I grew to love it.” Monicah Kitili reflects on her growth in energy modelling from being a student to a trainer of others, and what she would like to see in the future as East Africa tackles climate change and aims for sustainable growth.

I am a senior energy planner at the Energy & Petroleum Regulatory Authority (EPRA) in Kenya. The Authority is mandated to undertake technical and economic regulation within the electricity and petroleum sectors. My work centers on applying advanced tools and models to develop mid to long-term strategies that address current and future energy demands, while balancing resource availability with climate objectives. This entails comprehensive energy system analysis across both electricity and petroleum sectors. On the electricity side, we focus on demand forecasting as well as generation and transmission expansion planning, ensuring the adequacy of planned projects to meet future needs. Similarly, in the petroleum sector, we analyze demand for regulated products including PMS, AGO, JetA-1 and DPK to guide infrastructure planning and ensure reliable supply. Together, these efforts provide an integrated approach to energy planning that supports sustainability, security, and economic development.

My journey in energy modelling dates back in 2017 when I joined EPRA as an intern in the Energy Planning Department. I was fortunate to be part of a programme co-sponsored by the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners (NARUC) and USAID, which sought to empower more women to pursue careers in the energy sector. That opportunity not only introduced me to the field but also fuelled my passion for shaping sustainable energy solutions.

Soon after, I was absorbed into the department as an Energy Planning Officer, where I deepened my skills in energy system analysis and modelling. Over the next five years, I grew both technically and professionally, and my efforts were recognized with a promotion to Senior Energy Planner-a milestone that reinforced my commitment to driving impact in the sector through training the next generation of energy modellers.

When I first joined the energy sector in 2017, my entry point into energy modelling was through Kenya’s electricity master plan 2015-2035. The very first tool I worked with was LIPS XP/OP- a customized power system planning model used for generation operation and expansion planning in Kenya.

I quickly immersed myself in its application and complemented this with an Excel-based demand forecasting model, which gave me a solid foundation in linking demand projections with long-term supply planning.

In 2021, I had my first encounter with open-source models mainly OSeMOSYS through the country partnership between Climate Compatible Growth (CCG) and Government of Kenya through Strathmore Energy Research Centre. I took part in a series of in-person training sessions with CCG trainers to strengthen capacity in whole energy system modelling. This collaboration led to the successful development of Kenya’s full energy system model and the co-authorship of a peer-reviewed paper on mid to long term power planning using OSeMOSYS that was later published.

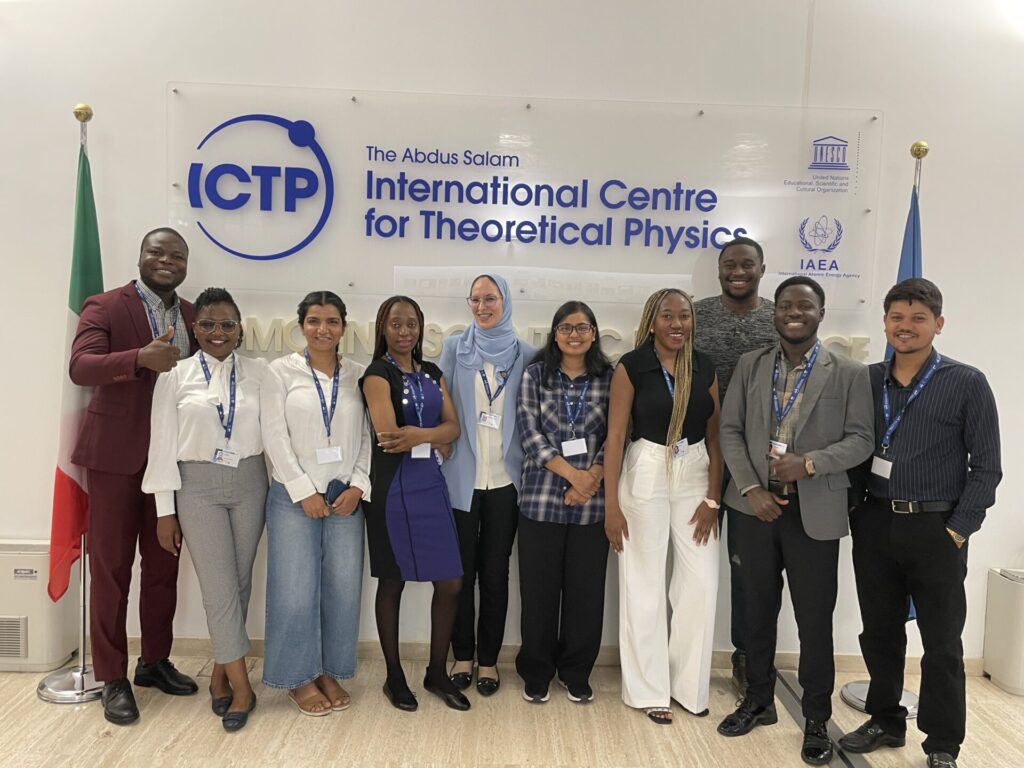

Since then, I have applied OSeMOSYS as the Lead Energy Modeller for Kenya’s Transition Beyond Oil and Gas Project. The study aimed at assessing Kenya’s readiness for a fair and inclusive energy transition, ensuring the country can meet its climate goals under the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) while maintaining energy security and economic stability. Alongside this, I have delivered trainings to MSc students at Strathmore University, staff across various ministries, and most recently through the Energy Modelling Platform–Global (EMP-G 2025). Through these experiences, I have been able to connect technical expertise with capacity building, contributing to energy modelling discussions at both national and international levels and supporting the growth of open-source modelling skills across the Global South.

What sets me apart as a trainer is my perspective from government. While I appreciate the academic side of modelling, my daily work allows me to connect models directly to real-world policy and operational challenges. I experience firsthand the issues that shape energy decision, from transmission constraints to unexpected generation outages. These realities constantly remind me that while models like OSeMOSYS can show a pathway to, say, 50% plus renewables, the real question is whether that pathway is practical and achievable in context. This ability to combine technical rigour with lived policy experience ensures that the training I deliver is both insightful and grounded in reality, strengthening the link between modelling and implementation.

At the EMP-G 2025, one thing that came out very clearly was the enthusiasm to learn energy modelling and to use results to inform policy. Equally important was the idea of integrating academic colleagues into policymaking, something often missing in Africa, where work is too often done in silos. Bridging this gap would allow policymakers to benefit from emerging academic insights while also testing them in the “real world,” ensuring that innovative ideas are not only explored but also translated into actionable solutions.

Thinking about the pace at which my country is responding to the climate crisis, the biggest challenge in Kenya and across Africa is not only inadequate modelling capacity but also poor prioritization. Too often, when technical analyses are not aligned with political priorities, policy makers overlook evidence-based recommendations in favour of political considerations. The task, therefore, is to present energy-related projects as part of a narrative that resonates strongly with government ministers: making the case in ways that are clear, compelling, and easier to digest rather than expecting decision-makers to engage with lengthy reports.

When it comes to energy modelling, our national team already has significant experience, though not specifically with some of the newer tools such as OSeMOSYS, OnStove and ONSSET among others. Strengthening the team’s capacity in these models and extending this knowledge to county-level planners remains a priority as Kenya transition to Integrated National Energy Planning. Another challenge we face is the high rate of professional turnover, which underscores the importance of succession planning. In this regard, I find CCG’s efforts to support integration of energy modelling into university curricula so that fresh graduates are better prepared to transition into government roles very valuable. This would help build a more sustainable and resilient pipeline of expertise.